Of all the questions I get about growing hosta the most common one is: which varieties will take sun - and how much sun is too much sun? Many shaded areas get SOME sun and choosing the right varieties for the conditions will be the difference between success and...

Maybe we won't talk about that.

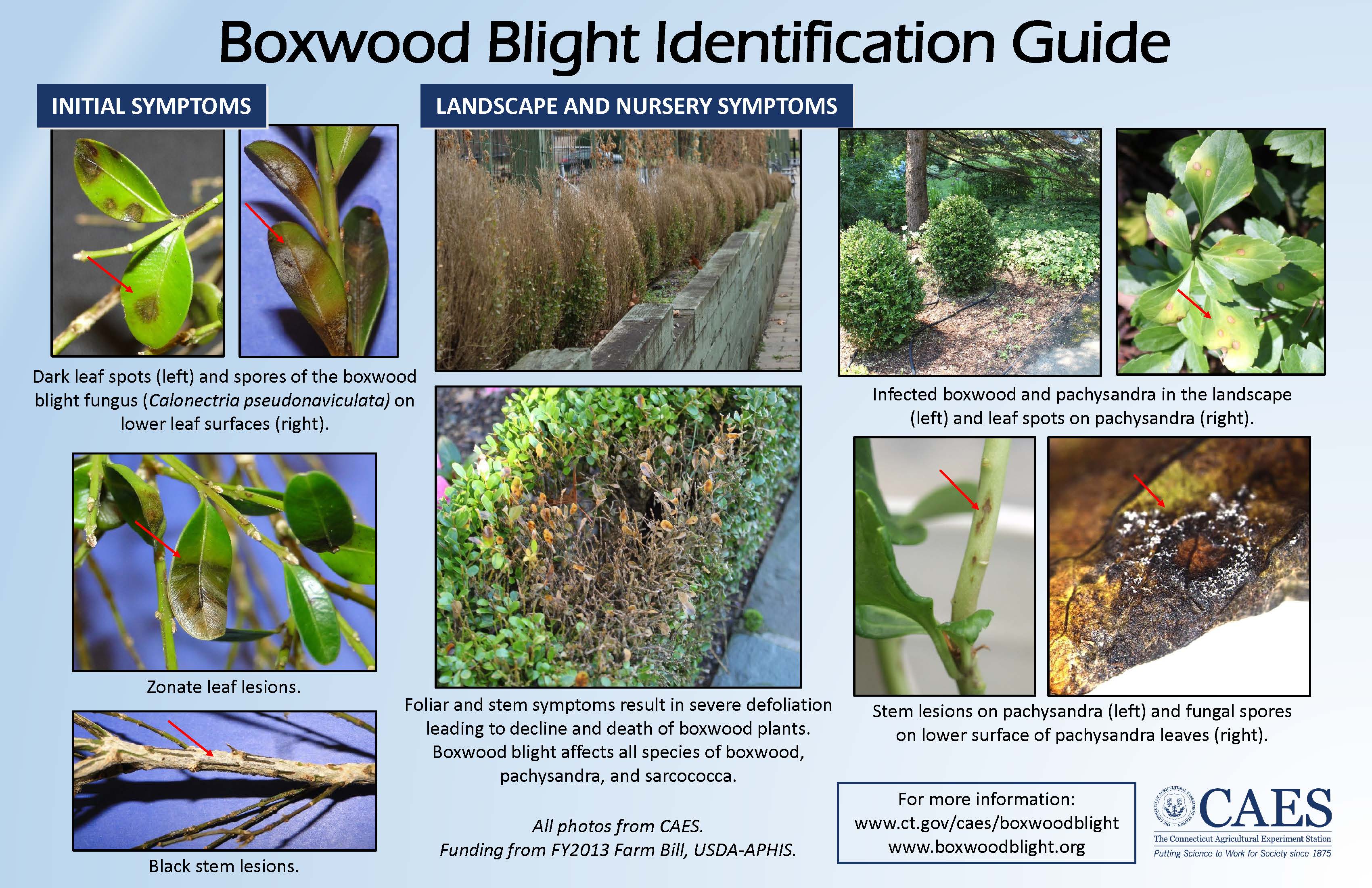

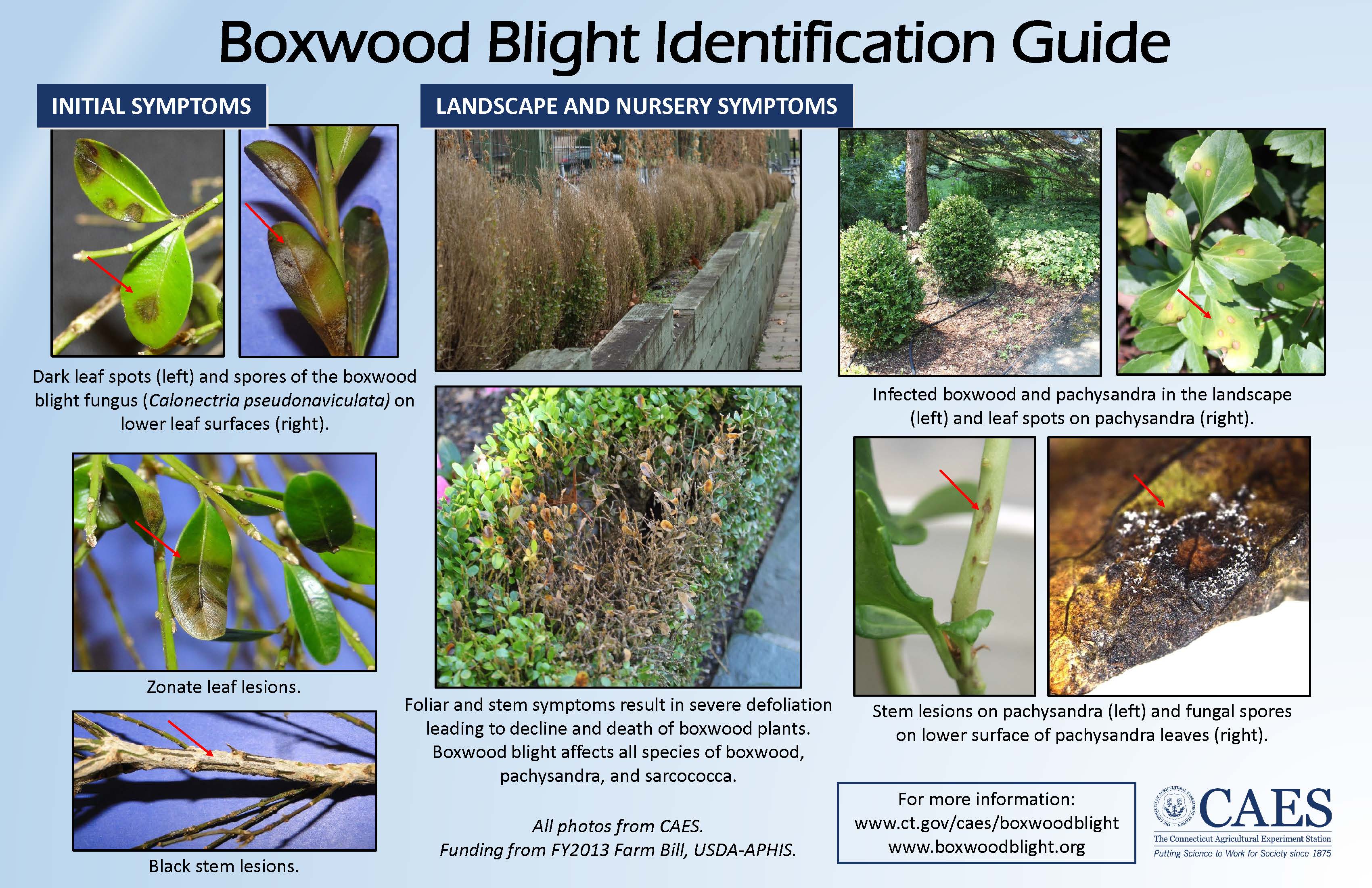

All hostas prefer to have morning sun and maybe some late afternoon sun. It is that midday sun that is the challenge. Sun tolerance, is to some degree, leaf-color related.

Hosta 'Guacamole'

Most hosta with whitish variegation will burn in hot afternoon sun. Those that have more green to chartreuse variegation will handle some of that midday sun as long as they are getting plenty of water. You should avoid putting blue hosta in the sun as the blue color is a waxy coating on the leaf and will melt off, turning your blue plants green. Golden hosta WANT sun. If they don’t get enough sunlight they will turn that sickly greenish-yellow chartreuse color. You know the one. Green hosta will typically take some midday sun, and I have found that the thicker the leaf the more sun they will take.

Hosta 'Vulcan'

Do you have a shady area that merges into a more sunny area and looking for some continuity? Here is a list of sun-loving hostas to fill in the sunny areas. Remember, soil moisture is key to keeping the plants looking good.

| 'August Moon' | Golden, medium to big size |

| 'Avocado' | Green with light green center, big size |

| 'Fragrant Bouquet' | Green with chartreuse edge, big size |

| 'Francee' | Green with white edge, medium size |

| 'Ginko Craig' | Small green with white edge, groundcover |

| 'Gold Standard' | Gold with green edge, medium to big size |

| 'Guacamole' | Light green with dark green edge, big size |

| 'June' | Gold with green edge and streaking, big size |

| 'Paradigm' | Gold with wide green edge, medium size |

| 'Patriot' | Green with white edge, medium size |

| 'Paul's Glory' | Gold with green edge and streaking, big size |

| 'Prairie Moon' | Gold, big size |

| 'Royal Standard ' | Solid green, medium size |

| 'So Sweet' | Green with cream edge, medium size |

| 'Spartacus' | Green with rippled gold edge, medium to big size |

| 'Sum and Substance ' | Lime-green, very big size size |

| 'Vulcan' | White with green edge, medium size |

Hosta 'June' (L) and 'Francee' (R)

Hosta 'Patriot'