Genetically modified foods have gotten quite a bad rap in the past few years, something I attribute to both a lack of knowledge and a multi million-dollar marketing campaign by the Non-GMO Project. That innocent looking butterfly that’s seemingly plastered on everything from salt to bread is an enormous spreader of misinformation. To begin with, salt does not have any genes to modify so a “Non-GMO” label is a bit misleading! I’ll try to dispel some of the more outlandish claims here.

Claim #1: Genetically modified produce is not as healthy as produce that is grown organically.

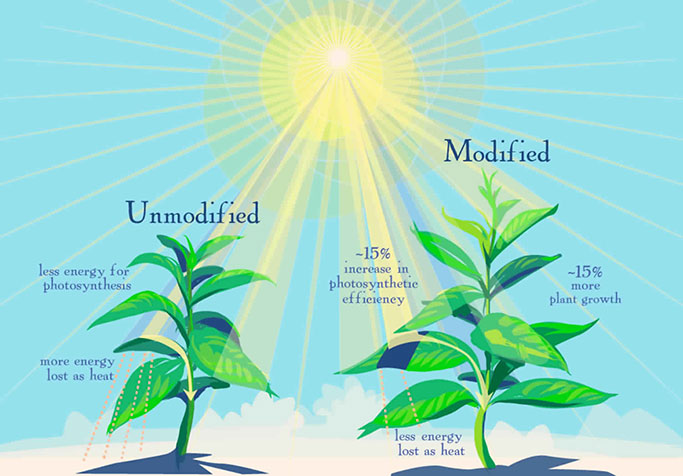

FALSE. There has been zero correlation between Genetic Modification and the health of food. Foods that have been genetically modified actually have a much more extensive testing and trialing process than traditionally grown foods. Biofortification can also result in a crop that has more nutrients than those that are traditionally grown. Ex. Golden Rice. (a)

Claim #2: Genetically Modified Crops are more expensive to cultivate.

FALSE. While it is true that there is a slightly higher price up front, “the economic advantages associated with insecticide savings and higher effective yields more than outweigh the technology fee charged on GM seeds.” (b)

Claim #3: The use of genetically modified crops only benefits large corporations.

FALSE. Globally, most genetically modified crops are grown by subsistence and small batch farmers solely for the purpose of providing for their families and the surrounding community. The recently approved GMO Cassava plant in Kenya produces a root with about 10 times more carbohydrates than the average cereal. It can also be grown in marginal and drought prone areas which account for about 80% of the land in Kenya. (c)

Claim #4: Genetically Modified crops use fewer pesticides.

TRUE. Most crops that have been genetically modified have actually been modified to be more resistant to diseases and pests. For example, with Genetically Modified corn, scientists engineered it to contain a gene that excretes a protein to kill invading pests such as the corn borer, thus eliminating the need to be sprayed with an insecticide (d).

(a) Ingo Potrykus, Lessons from the ‘Humanitarian Golden Rice’ project: regulation prevents development of public good genetically engineered crop products, New Biotechnology, Volume 27, Issue 5, 2010, Pages 466-472, ISSN 1871-6784

(b) The Economics of Genetically Modified Crops, Annual Review of Resource Economics, Vol. 1:665-694 (Volume publication date 2009) First published online as a Review in Advance on June 26, 2009

(c) Kenya approves disease-resistant GMO cassava

(d) Gewin V (2003) Genetically Modified Corn— Environmental Benefits and Risks. PLOS Biology